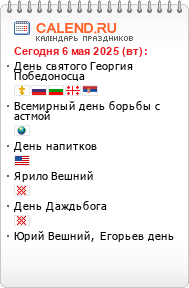

Richard Carpenter

Robin of Sherwood

A magical retelling of the legend of Robin Hood based on the new ITV series

[p.1] Puffin Books

ROBIN OF SHERWOOD

‘Robin Hood must be destroyed,’ whispered the Baron. ‘We are all agreed on that. Though perhaps for different reasons.’ He leant forward. ‘I know he will come to me and I know he will come alone.’

Ever since Robin Hood had fled as an outlaw into Sherwood Forest, he too had known that a confrontation with the vile Baron de Belleme was to come. The Baron was a man feared the length and breadth of the land for his cold-hearted cruelty and the demonic powers he used to keep his servants enslaved. Only one man could possibly ever break the Baron’s hold on England, and that man was Robin Hood, come to Sherwood to fulfill the ancient legend of Herne the Hunter, and to fight against the oppression of the weak, the sick and the poor.

As the Baron’s net tightens around Sherwood, Robin Hood’s outlaws and their friends, Friar Tuck and Maid Marion, daily run the risk of capture, torture and death. Time after time, Robin and his men slip through the enemy’s grasping fingers, only to vanish again in the depths of the forest. But then the Baron plans the most horrifying trap of all...

The swashbuckling adventures of England’s most famous hero have been cleverly retold by Richard Carpenter, who is well-known for his previous successes both on television and in books, including Catweazle, The Ghosts of Motley Hall and Dick Turpin.

[p.3]

RICHARD CARPENTER

ROBIN OF SHERWOOD

PUFFIN BOOKS

[p.5]

INTRODUCTION

Another Robin Hood book when there are already so many seems to need a bit of an explanation. This version began life as a television script, and I owe a great deal to everyone who worked on the series for their creativity and help. In particular I’d like to thank Paul Knight who produced it, Ian Sharp who directed it, and the splendid and enthusiastic cast who brought it all to life.

I didn’t want to make it a history lesson but I have followed recent tradition and set the story in the reign of Richard I.

There is no magic in the original ballads and almost no reference to the popular idea of Robin fighting against oppression. But the story has been snowballing for over seven hundred years and has grown with each retelling. That’s what has kept it alive. I hope my version remains true to the spirit of Robin Hood while at the same time providing a few new ideas of my own.

RICHARD CARPENTER

[p.6]

In the days of the Lion spawned of the Devil’s Brood, the Hooded Man shall come to the forest. There he will meet Herne the Hunter, Lord of the Trees, and be his son and do his bidding. The Powers of Light and Darkness shall be strong within him. And the guilty shall tremble.

PROPHECIES OF GILDAS